Economic and Housing Research

Original research and analysis on housing trends, the economy and the mortgage market

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – January 2025

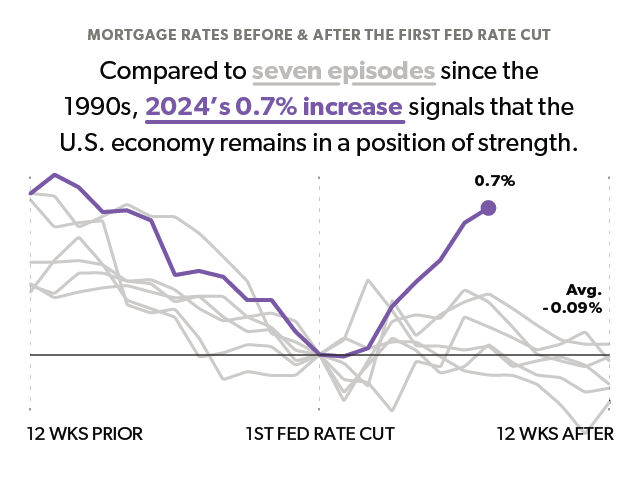

The U.S. economy grew at a stronger pace than initially estimated in the third quarter of 2024 while the labor market remains resilient.

Read MoreEconomic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – January 2025

-

Spotlight | December 20, 2024

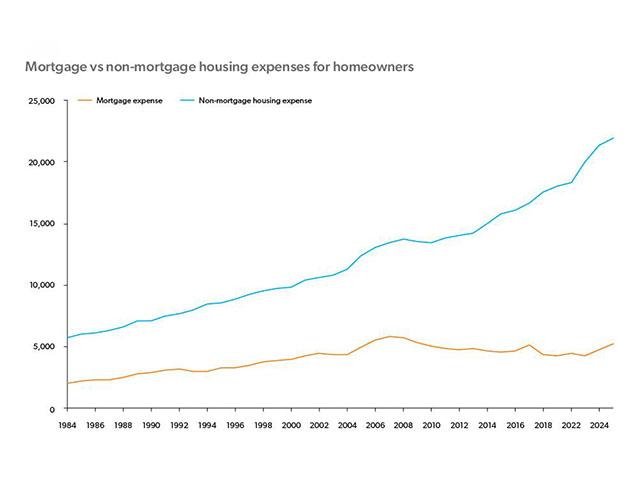

Homeowner vs. Renter Spending in an Era of Rising Housing Costs

Homeowners locked into low mortgage rates have shielded themselves from rising interest rates and house prices, whereas renters do not have the same advantage. More

-

Outlook | December 20, 2024

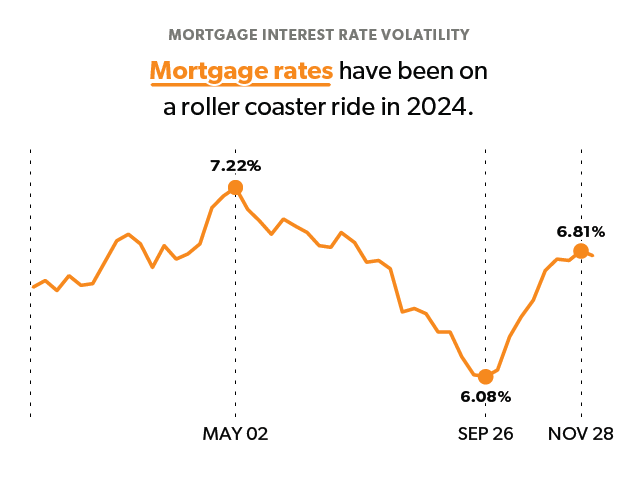

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – December 2024

The U.S. economy remains robust with strong Q3 growth driven by consumer spending. More

-

Spotlight | November 26, 2024

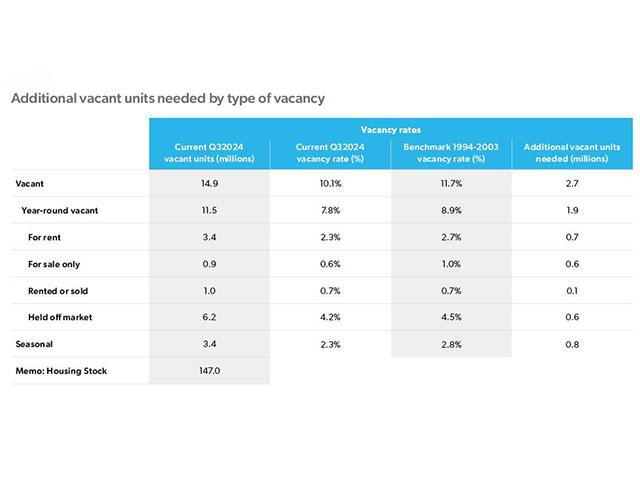

Housing Supply: Still Undersupplied by Millions of Units

The housing market continues to be plagued by a shortage of units for rent and for sale. We estimate the housing shortage is 3.7 million units as of 3Q24. More

-

Outlook | November 26, 2024

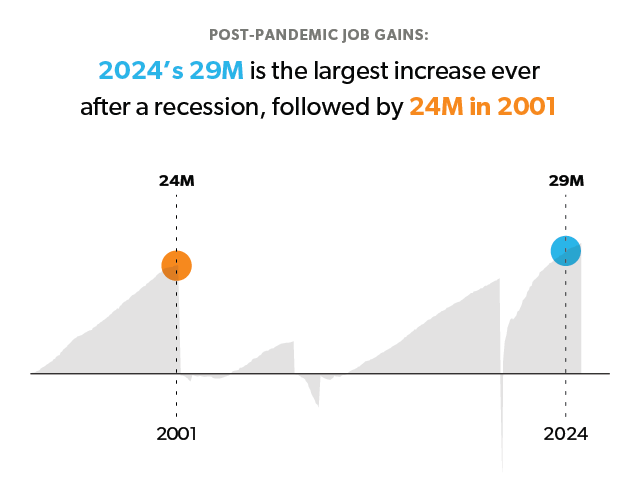

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – November 2024

The U.S. economy remains resilient with strong Q3 growth even as the labor market moderates. More

-

Research Note | November 12, 2024

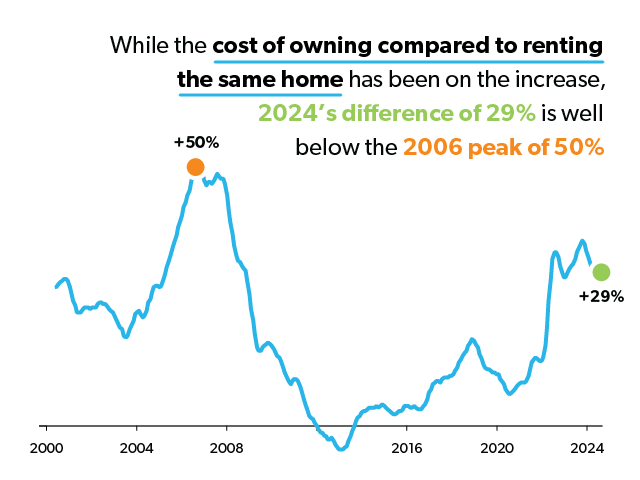

The Decline in Relative Housing Affordability and the Impact on Homebuyer Search Behavior

In this analysis, we use actual, detailed transaction data on rents, home prices, and mortgage payments for individual homes and borrowers to produce a new relative affordability measure. More

-

Spotlight | October 18, 2024

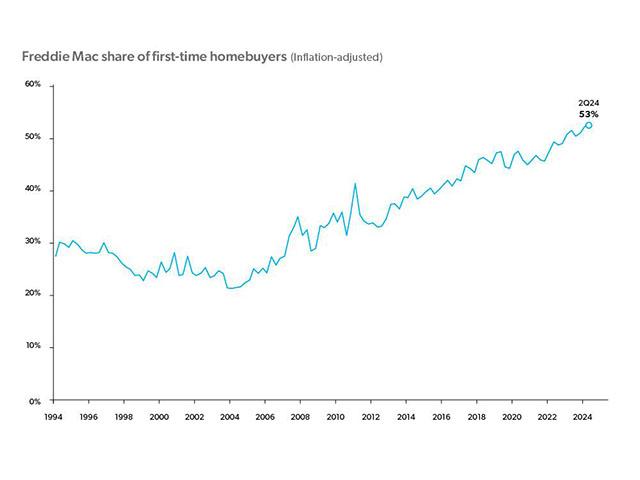

First-Time Homebuyer Activity

First-time homebuyers are increasingly driving demand in the housing market. However, they face headwinds in affordability, supply and overall economic conditions. More